On Thursday, September 18th, I found myself heading uptown to The Met. A couple of days before, I had read an article in Time Out on the best exhibitions in New York on display right now, and lo and behold, in first place was Man Ray: When Objects Dream at the Met. When I asked my dad, one of the most creative and visually intellectual people I know, if he thought I should go see Man Ray, his text message answer was a simple “Yes” and “Cool.” That was all the confirmation I needed.

My best friend, who studies photography, decided to join. She is fascinated by Man Ray's use of light, and wanted to go with me to draw inspiration for her own work. With everything: the Times Out article, my dad, and her, pointing toward this show, my expectations were anything but low.

When I first arrived at the exhibition, I felt very drawn in. The space was surprisingly dark, partly, I assume, to protect the light sensitive works, but also because it set up a mood completely different from the rest of the Met. The museum's usually bright, airy galleries filled with light sculptures gave way here to a more intimate, shadowed, and almost intimidating atmosphere.

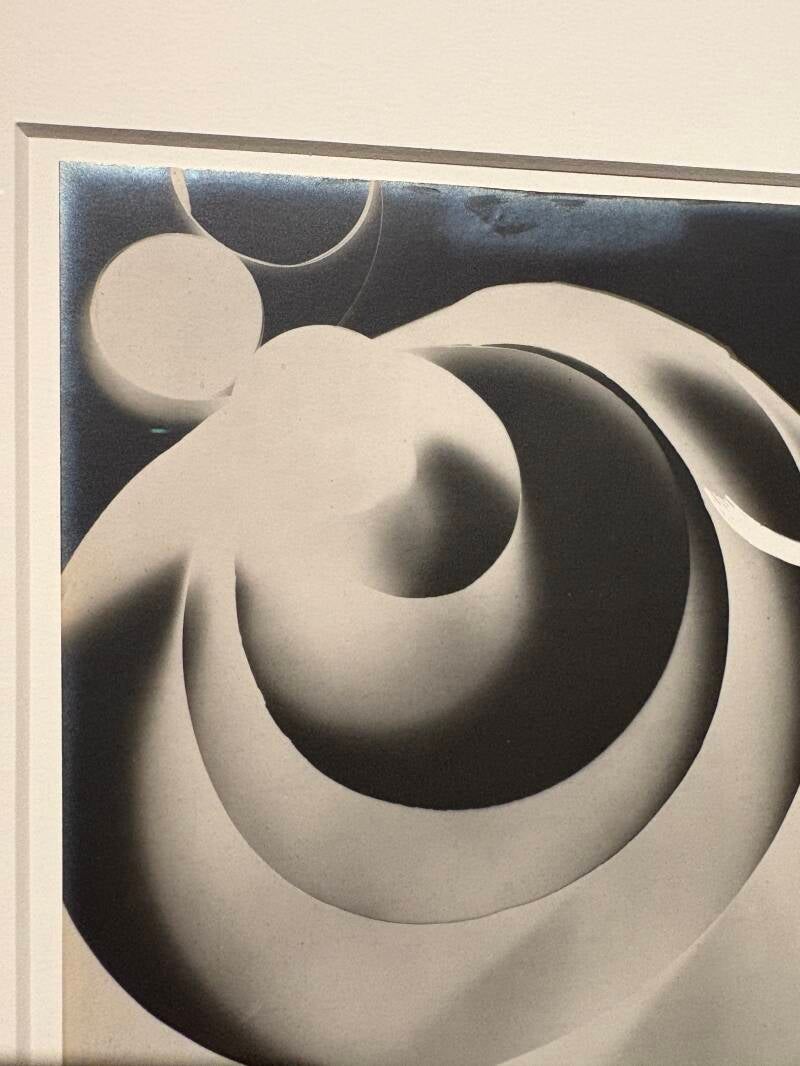

Man Ray was most active in the early to mid-20th century and was far from an ordinary artist. In some ways, he didn’t feel like an “artist” at all. He was more like a magician, or at least a visionary. He loved to experiment and to play with art, something that was not always welcome in the sometimes rigid, pretentious art world. When Objects Dream highlights many phases of his work, but it especially focuses on his invention, the “rayograph.” First of all, genius name. Second, an incredible experiment. It’s a twist on a much older photographic technique: making pictures without a camera. I was baffled. How on earth does that make sense? Instead of using a lens, you place objects directly onto a sheet of sensitized paper, expose it to light, and then, as if by magic, the image appears.

Understanding this process was one thing, but walking into the space and being greeted by Champs délicieux (Delicious Fields) (1922), a grid of twelve rayographs, four across and three down, on a black wall was something else. They seemed swallowed by the surrounding dark space, which gave them an ethereal quality. It really felt as if we were being invited into Man Ray's own darkroom.

Except for all the wonderful Rayographs that filled the exhibit, there were three works that I found especially appealing when walking around the space: Facsimile of Revolving Doors (1913-1919), Lampshade (1921), and Obstruction (1920, edition 1961).

Man Ray’s array of Facsimile of Revolving Doors (1913-1919) was one of the first works that filled the exhibit. It was interesting that after walking into darkness came light and color. They were different from what I expected of Man Ray. These were very colorful, not black and white. But even though the color surprised me, everything else was very on par with what he usually did. These were from the beginning of his career, and they really capture his experimental spirit.

The works are very modernist. They play with geometric shapes such as triangles, circles, and squares, and they use primary colors like red, blue, and yellow. The shapes almost look like shadows, while the colors remind me of the colors from light waves.

In each of the prints, there is some sort of form dominating the image. They are very abstract, yet they all tell a story. You can see what you want to see, look for what you want to look for. There are many symbolic meanings in each. I like what Man Ray does too, naming these works after words such as mime and orchestra.

I think you can see in these works how they lay the groundwork for some of his later works in photography.

In a glass container in the corner of a small room is Man Ray’s Lampshade (1921). I was very fascinated by this artwork which was made from a broken lampshade placed on a dress stand. I loved the sculptural confusion it created. When looking at it from the front, it seemed as though it took up much more space in the back, but it was almost flat. It looked as if it moved and occupied space even though it didn’t. It became an illusion, tricking my eyes.

I later read that it was discarded shortly after being made because someone thought it was trash. That really confused me, how could anyone ever think this was trash? To me, it perfectly captures what art should be: mixing the ordinary with the fine and turning found objects into something sculptural and expressive.

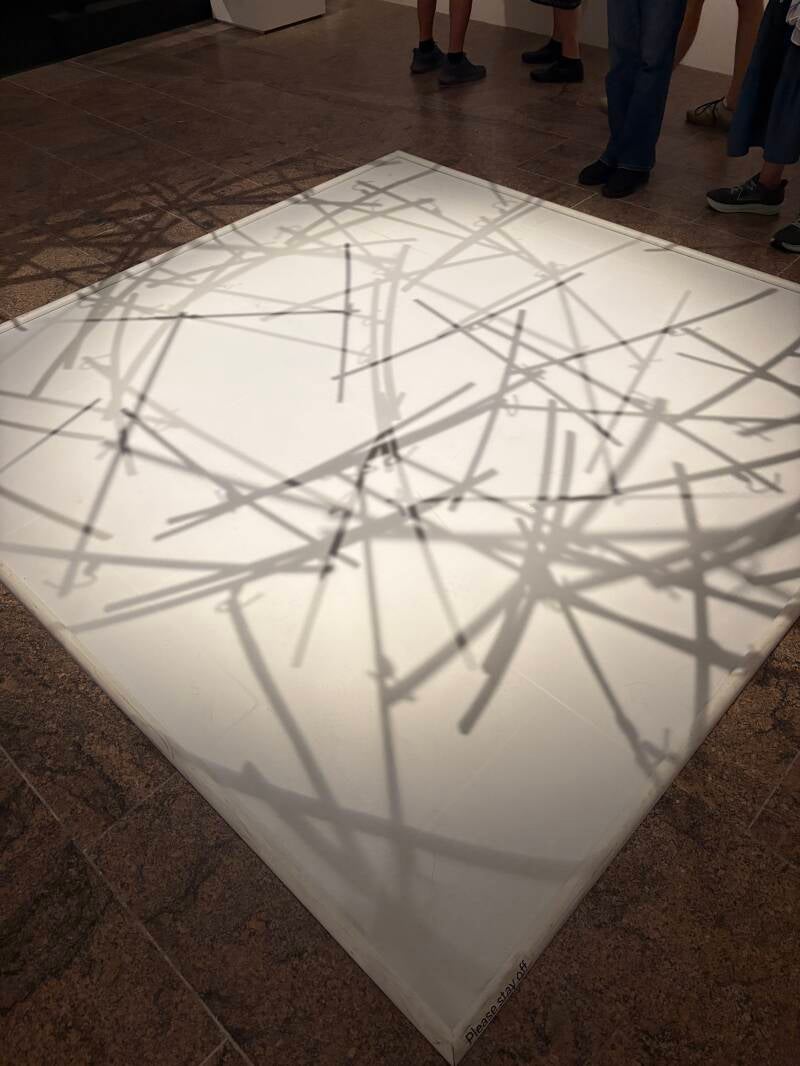

My favorite piece in the exhibition was Obstruction (1920, edition 1961). I first noticed it from a distance and was immediately intrigued. It was a kinetic object, swaying with the movement in the room. I watched as people stood beneath it and blew on it, making it sway even more. In that moment, that artwork became interactive, and the viewers themselves became part of the piece.

The object itself looks like a chandelier but is made entirely of brown wooden hangers. So it could function as a hanger; I could imagine myself hanging things on it.

The shadow it cast on the floor was beautiful. Creating a separate artwork. It shifted and danced as the sculpture moved, creating long, ghostly stripes that no longer looked like hangers.

I loved that Obstruction (1920, edition 1961) felt so experimental yet still so graceful and poised. It transforms the simple everyday hanger into something imaginative, inviting people not just to observe the art but to engage with it. For me, that playful spirit, balanced with elegance, is precisely what Man Ray’s work is.

Create Your Own Website With Webador